More Techie Stuff On Microphones – Frequency Response

So I asked a bunch of people what they thought of Part 1 of my microphone article. It seems most people liked it, but some people thought it was too techie (Part 2 will not be so techie, so stay tuned), some people thought it was not techie enough and wanted to know lots more, and some people thought it was about right. I guess on average it was about okay. A lot more could be said about microphones, so especially for you tech-heads, here's an addendum.

A person might well ask, what are the main aspects of microphones that would make you choose one over another? (Go ahead, ask me.) Well, there's the price, size, reliability, the looks, pickup pattern (I talked a little about cardioid, hyper-cardioid, figure eight, and omni-directional patterns in Part 1), sensitivity, low noise and perhaps most importantly, how it sounds. Of course there are many different applications of microphones, like broadcast, live and studio situations, and many different sound sources, like drums, electric guitars, acoustic instruments, piano, voices, horns, and so on. That's too much to cover, so I will talk primarily about vocals and acoustic instruments, and "how it sounds". In using a mike, the goal is normally to pick up the vocal or instrument as accurately as possible, so that it sounds most natural through the sound system. Knowing that any sound is composed of a wide range of vibration frequencies (sound audible to humans ranges from about 20 Hz to 20 kHz at best), the frequency response of a microphone is a useful measure of the accuracy of the mike, and you would expect (perhaps?) this frequency response to be very flat, so that all audible frequencies are reproduced equally.

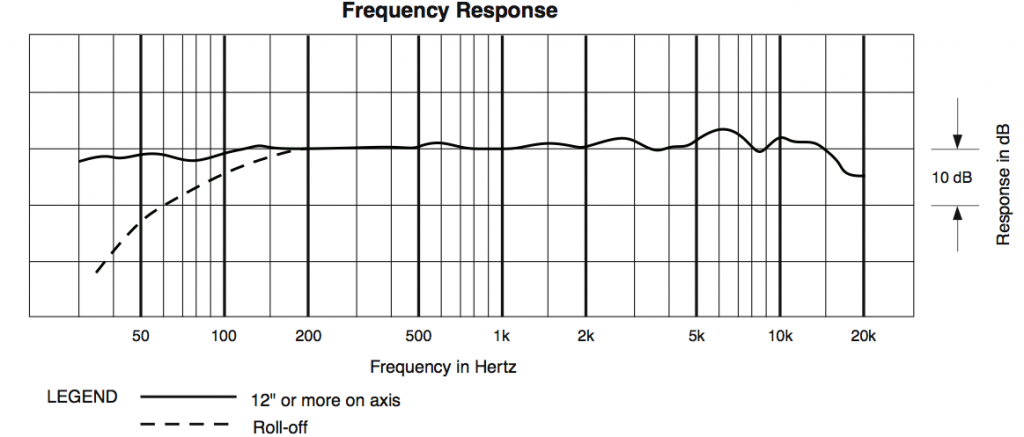

Let's look at the frequency responses of a few commonly-used mikes. Fig. 1 shows the typical response of the AT4033/CL, a cardioid condenser mike favoured by Del McCoury, and many bluegrass bands. Notice that it's not really flat? There are a few bumps up around 6 kHz and 10 kHz. 10 kHz is an area of the sound spectrum that can be described "crispy," "bright," "breathy," and so on. This emphasis in response here can help bring out bright aspects of strings and voices. Intelligibility of a vocal resides between about 4 to 6 kHz. The response drops off above 15 kHz and below about 30 Hz. Frequencies above 15 kHz are really quite high pitched, and most people can't hear much of it anyways, so it's not useful to reproduce (and it's harder too). The lowest note, E, on a string bass is about 42 Hz, so you don't need much below that either. You need some response at the bottom, however, so keep the fullness of the notes intact. Note that there is a roll-off curve too. Most mikes have a low rolloff switch (also called high pass) to attenuate the lower frequencies. There are two main reasons for this. First, a lot of low frequency noise can appear from stage rumbling and mike handling, so rolling that off is very helpful and doesn't harm the sound. Second, pretty much all cardioid pattern mikes have a problem (or benefit, depending on your viewpoint) called proximity effect. That is, the closer you get to the mike, the more pronounced the low frequencies become. So rolling that off can compensate when you're singing or playing quite close to the mike.

Frequency response of AudioTechnica AT4033/CL

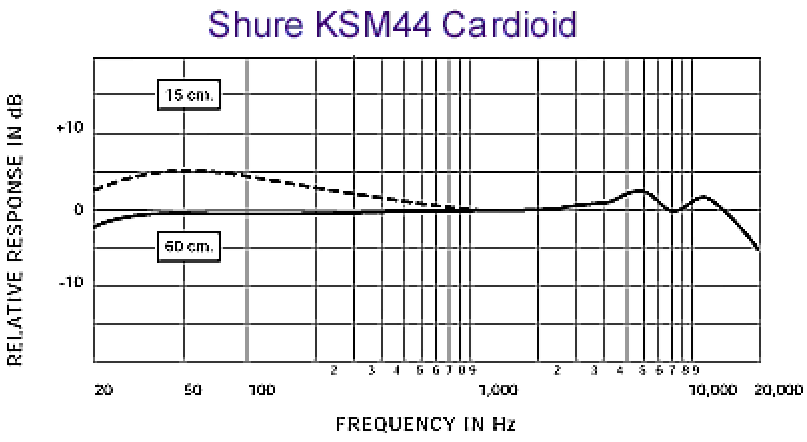

Fig. 2 shows the cardioid response of the KSM44, another popular bluegrass condenser mike. Like the AT4033/CL, there are two bumps up at about 6 kHz and 10 kHz. This plot shows the proximity effect quite well: the low end response is quite high even 15 cm from the mike. Fortunately this mike has a three-position low frequency rolloff switch to compensate.

Frequency response of Shure KSM44.

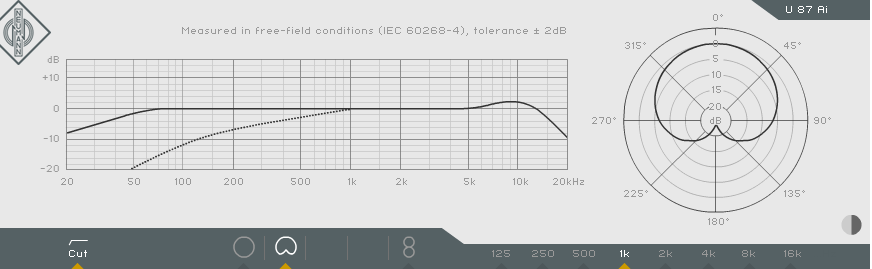

Fig. 3 shows the frequency response of the Neumann U87Ai, one of the most commonly used mikes in recording studios (the studios that can afford them anyhow). This is a smoothed curve - individual mike responses usually are much bumpier. Again, there's a bump up around 8 to 10 kHz, and pretty drastic rolloff starting at 60 Hz. With the low cut switch on, the rolloff is even more dramatic.

Frequency response of Neumann U87Ai.

Finally, Fig. 4 shows the response of the Shure SM81, a small diaphragm condenser mike favoured for miking acoustic instruments and cymbals. Notice how flat the response is all the way from about 40 Hz to about 15 kHz.

Frequency response of Shure SM81.

How do mike manufacturers achieve different results? The are a few factors. First, there is the diaphragm design. The diaphragm is the part that vibrates with the sound. A large diaphragm (about 1 inch in diameter) generally has a good low frequency response, but might not move fast enough to capture high frequency transients that happen with bright guitar strings and cymbals. Small diaphragms capture high frequencies and transient detail better but may suffer in the low end. There are also medium sized diaphragm mikes that offer a good compromise. Another factor is the acoustic design of the capsule mounting and housing. Changing the shape of the housing and the positioning of the capsule can change the acoustic characteristics of the mike. Finally, the electronics inside the mike (especially in the case of condenser mikes) have a significant effect. Two main classes of electronics in condenser mikes are tube mikes and FET (field effect transistor) mikes.

I started out by supposing that a "good" mike should have a flat frequency, but it turns out that the best mikes chosen by most recording engineers and musicians do not necessarily have such a characteristic. The frequency response is an objective measure, but really people choose equipment subjectively to suit the task, and according to what they want to hear. This leads into a whole new topic called psychoacoustics, which is about how the human ears and brain perceive sounds. Read about that here.

In summary, it looks like a lot of good mikes have similar characteristics, but there are numerous subtle differences too. Knowing that most mikes have been designed carefully to have particular characteristics for a particular job, you realize that you shouldn't have to do much equalization to get a good mike to sound good. Mike placement, however, can make a huge difference in how things sound, and that's a whole 'nother topic too.

A person might well ask, which mike should I buy? (Go ahead, ask me.) Um ... it depends on many things: budget, application, personal preference, etc. That sounds like another whole 'nother topic. My best advice for now: buy the best one you can afford, stick to some good and proven brands (Shure, AKG, AudioTechnica, etc.), be suspicious of hype and myths, and don't worry about it too much.